It is over a year since Jon Barwise passed away. There is still a quarry-sized crater in the hearts and minds of many at Indiana University.

Jon Barwise came to Indiana University as College Professor, just over ten years ago, in the fall of 1990. He was a restless man, and had a reputation for moving every five to ten years. Still, people were amazed that Jon could be recruited from Stanford; and there were some, around the world, who weren't sure how long he would stay. But there was no special trick to it. Jon, his wife, Mary Ellen, and their then-young daughter Claire, were mid-westerners. They were coming home. Also at Indiana University he was able to help build the kind of interdisciplinary environment for logic that he had been searching for throughout his professional life.

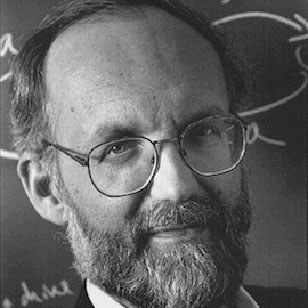

Bloomington did become home to the whole family -- even to the grown children, Melanie and Jon Russell, who lived elsewhere. Jon and Mary Ellen quickly became totally involved in the Bloomington community, making many friends. Soon after they arrived they built a wondrous house, which Jon partly designed, spilling over into a wooded valley, on Hunter's Glen. But Jon, a life-long walker, wanted to be closer to his friends, his work, his community. And so in 1997 they moved to a home on Hawthorne, just a stone's throw from campus. There can't have been anyone in the neighborhood who didn't know the site of this tall, lanky, bearded fellow, striding to and from work. Or who hasn't noticed the bench, made by his friend Ken Vardoner, that Jon and Mary Ellen had installed on the sidewalk in front of their house -- so that people could stop, sit, stay a while. Jon's favorite picture of himself, at the end, was one in which he was stooping over the brand-new bicycle of a very young friend, who was just learning to ride on that beloved sidewalk. The child probably never knew that this tall man was one of the most formidable logicians in the world.

It was that enduring humanity that made Jon's recruitment such an unparalleled success. Not only did IU gain a world-class researcher and a gifted teacher, but it gained a first-rate citizen of the university. That Jon's work was interdisciplinary is evidenced by his appointment in five departments and programs: Philosophy, Mathematics, Computer Science, Cognitive Science, and Linguistics. In addition, recruiting his instincts as a carpenter and builder, he imagined and helped to create any number of institutions. The Program in Pure and Applied Logic, the Logic Seminar, and the Visual Inference Laboratory are just three IU programs that owe their existence to his vision. And he played a very significant role in shaping the intellectual vision behind the new School of Informatics.

While at IU, Jon served on countless campus and university committees, not just having to do with his subject matter of logic, computers, and information technology, but also teaching, tenure, searches, reviews, etc. He would occasionally complain to close friends about his service commitments -- not because he resented the work, or thought it unimportant, but because he feared he was spreading himself too thin. His was a heart that had trouble saying "no," and he always sought out service roles that made a difference. Some faculty seem to sing in a single key; Jon could sing a trio by himself -- of research, teaching, and service. He was that ideal faculty member, so often envisaged but so rarely encountered, whom deans love to hold up as the very standard of what it is to be a university professor.

Jon was author or co-author of 11 books and nearly 100 papers. He was world-renowned for his research in logic and its interaction with other fields. His early work, in pure logic, was primarily concerned with model theory and higher recursion theory. But his restlessness infected his work as much as his life; his web page approvingly quoted Abraham Robinson on how it is good to move jobs or change research topics every five years. And so he branched out. In philosophy, he focused on the implications of epistemology, metaphysics, and the philosophy of language for the foundations of logic and mathematics. In linguistics and computer science, he set out to develop a theory of information rich enough to support an understanding of discourse and computation. This latter work, cut tragically short, was an effort to distill, into a single mathematical theory, a theme that had underwritten his whole life's work: how to understand the semantic content of information, independent of form -- in language, thought, computers, and graphical notations, and in systems that transform information between and among different representational forms.

Over the years, the body of Jon's work developed a legendary status. "From the European perspective," said Johan van Benthem (of the University of Amsterdam and a colleague at Stanford), "Jon was one of those people who define a whole field. Many students and colleagues on other continents who had never even met him felt their work shaped by the force of his ideas and personality -- because of the power of his publications."

But whereas many who achieve that kind of prominence do so as solitary individuals, Jon Barwise was an absolutely extraordinary collaborator. Jointly-authored works in philosophy are rare; but more than half of Jon's books, including virtually all the major ones, are the products of joint labor: with Sol Feferman, John Perry, John Etchemendy, Larry Moss, Jerry Seligman, and Gerry Allwein. Throughout his life, colleagues and graduate students (both at IU and elsewhere) were involved in his many projects. He even wrote a play with another Bloomington friend, Michael Smith. In the weeks after his passing, many of these friends and collaborators poured into Bloomington, some from half way around the world. His funeral and memorial services were thronged, not by students and admirers, who had looked up at Jon from a distance, but by *friends*-- academic, non-academic, anyone who had walked for a bit, on a path, alongside Jon.

That same spirit of collaboration infused his teaching -- an area to which Jon devoted as much effort as research. He was quick to volunteer for undergraduate courses, and, while no automatic conveyer of praise, delighted in opening minds to the rigors of analytical thinking. With John Etchemendy, a life-long friend, he developed several software packages for teaching logic, which are now used around the world (for which they won the Educom Medal). And he himself remained a student, his whole life: learning not just new intellectual fields, but to paint, to paddle, to fly. Even during his final year, when Jon had cancer and knew he probably wouldn't live long, he strove passionately to understand what was happening, and held together an extensive community of family, friends, and colleagues with an inspiring electronic journal. In the words of Irene Scott, the wife of Dana Scott (one of his teachers), "Jon taught us how to die."

It is easy to brag about Jon's accomplishments, but it is difficult, for those of us who knew him -- and there are many -- to put our feelings into words. Plus, he had an almost ethical love of plainness and simplicity, and would be embarrassed if we tried. Suffice it to say that a year is as nothing, in a loss of this magnitude. Jon is truly missed -- in Bloomington, at Indiana University, at Stanford University, and throughout the world.

J. Michael Dunn

Brian Cantwell Smith

March 27, 2001

Jon Barwise was born in Independence, Missouri on June 29, 1942, and passed away in Bloomington, Indiana, on March 5, 2000. He received a B.A. in Mathematics and Philosophy from Yale in 1963, and a Ph.D. in Mathematics from Stanford University in 1967. He is survived by his wife, Mary Ellen, of Bloomington, and three children: Melanie, of Madison, Wisconsin; Jon Russell, of Portland, Oregon; and Claire, of Bloomington.

This resolution will become a part of the minutes of the Bloomington Faculty Council.

Homepage on archive-it.org